Turbulent times continue to exact a heavy toll on both people and planet, as the world attempts to tackle the climate emergency, the ongoing collapse in biodiversity, social unrest and war, and economic crises. Faced with this unprecedented combination, how do we heal the Earth? The place to start is by healing ourselves and our communities.

‘Self-care’ is starting to gain traction as an act of resistance and collective kindness, informed by changing belief systems. People are looking for reassurance in something bigger than themselves, turning to ancestral practices, albeit often delivered digitally. This is leading to a deeper appreciation for the ways in which mind and body and the natural world are connected – and better conversations about all humans, not just the privileged few, being part of the natural world, rather than above or outside it. This reconnection to nature also challenges accepted norms within ecological thinking. Understanding our own biological cycles and nature’s rhythms is bringing about a shift from ‘sustainability’ to ‘regeneration’ and a desire for a ‘flourishing’ planet.

Self-care is starting to gain traction as an act of resistance and collective kindness, informed by changing belief systems. People are seeking reassurance in concepts bigger than themselves, turning to ancestral practices and ancient wisdom. This is leading to a deeper appreciation of the ways in which mind and body and the natural world are connected – and better conversations about all humans, not just the privileged few, being part of the natural world, rather than above or outside it. We explore this further in our Industry Insight feature, which introduces pioneers who are starting to make mental wellness available to all.

This reconnection to nature also challenges accepted norms within ecological thinking. Understanding our own biological cycles

and nature’s rhythms is helping us understand that aiming at sustainability is no longer enough: we need to turn to practices that

enable regeneration and a planet that can flourish and re-grow.

In the Mind, Body, and Soul issue, we explore the roles of art, design, technology, and creativity in cultivating nurturing, regenerative,

and nourishing environments that heal souls, minds, bodies, communities – and, moving outwards from our innermost selves to our wider surroundings, ultimately heal the planet.

Soul

“I incorporate spiritual practices into my work-life, using a tarot deck to help decision-making, casting spells for success, and calling on deities to guide me,” says Annie Ridout, the author of upcoming book Raise your SQ.

She is not alone.

SQ refers to spiritual intelligence, and Ridout believes spirituality, magic, and what Generation Z refers to as “woo” are becoming more mainstream as we search for “more connection and magic in our lives.” Platforms such as New Mystic, popular with Gen Zers, combine magic with technology, bringing folklore, Indigenous knowledge, plant healing, and psychedelics together with non-human intelligence and artificial intelligence, curated by artists, and delivered digitally. Kate Northrup, the author of Do Less, advises

businesswomen to plan around menstrual cycles or moon phases – and millions check astrologer Chani Nicholas’s eponymous app daily.

Witchcraft or wiccecrœft once simply meant rituals of natural cure, herbal remedy, and spiritual wellbeing, usually performed by women. They clashed with Christian, patriarchal and capitalist belief systems, and were othered and subjugated, in a long

history traced by archaeologist and medieval historian Alexander Langlands in his book Cræft – An Inquiry Into the Origins and True Meaning of Traditional Crafts. Their resurgence can be seen as a feminist reclamation. “To be a witch is to embody defiance

and rebellion against the injustice that masculine systems have created,” Tina Gong, the developer behind tarot app Golden Thread, told Dazed Digital.

As the role of these “masculine systems” – and the resulting marginalisation of Indigenous knowledge – is recognised in the biodiversity crisis, Western environmentalists are looking towards older ways of connecting with nature.

“The word animism refers to something so commonplace … in Indigenous cultures, that most don’t even have a word for it,” says author and mystic Toko-pa Turner in her book Belonging. “It is the foundational belief that … all things are imbued with a soul.” And

it is harder to exploit something with a soul. Spiritual ecology is an emerging field that recognises this spiritual facet to conservation. Online communities such as the Spiritual Ecology Study Club offer teachings on the subject with the aim of “reuniting people, the living world and the sacred.

Mind

Research has long shown that nature is good for our mental health, and new evidence suggests that the quality of our relationship to nature is important – “connectedness” is what we’re aiming for, according to a 2021 report by the UK Mental Health Foundation. “Setting aside one minute a day to pay attention to your breath and remember that we give plants carbon dioxide with each exhale and in return they give us oxygen helps us remember that we are children of Earth’s ecosystem,” says somatic coach Tamu Thomas

The Mental Health Foundation report also found that for women, people of colour, and those with disabilities, “nature spaces may feel inaccessible or less enjoyable because they are not safe.” Apps such as Spoke democratise access to mindfulness support, while The Breathing App and Open similarly offer meditation at the touch of a button – accessible technology, as well as nature, can help people find peace.

Others are turning to the judicious use of microdosing. While psilocybin remains illegal in many countries, various research papers have found it effective in reducing anxiety and depression – and improving mood and focus for some users. Those seeking to experiment are turning to psychoactives such as those offered by Gwella, which draws on mushroom-derived psychedelics, or PLANT, a dispensary whose name is an acronym for Peace, Love and Natural Things. And for 100% legal alternatives, there are digital offerings that prom�ise similar effects; for example, The Dream Machine, by Collective Act, uses music and light to mimic hallucinogens – participants each “see” something different behind their own closed eyes.

Body

Today’s self-care practices encompass natural ingredients once considered “alternative” and comprise a more holistic, ritualised experience for body and mind. Inspired by traditional Chinese medicine, Herbar has released a mushroom based face oil for “skinimalists”, and skincare and fragrance brand Haeckels packages seaweed to bathe with. Biomaterial specialist Rosie Broadhead’s undergarments promise the bioactive therapeutic effects of seaweed, as people pay more attention to what is absorbed into the biggest organ of their body – their skin. Our Wearable Wellbeing feature explores Broadhead’s work, alongside that of other innovators

delivering wellbeing benefits via the skin

The exclusion of historically marginalised groups extends to bodily healing too. Youth practitioner Ebinehita Iyere, the founder of Milk Honey Bees, a healing and empowerment space for Black girls, told Dazed Digital: “We have to hone in to inclusive wellness practices that celebrate us.” Such products include Liha Beauty’s Oju Omi Cleansing Mud and the brand’s Gold Shea Butter. Shea butter is called women’s gold in west Africa, co-founder Liha Okunniwa told Planet Woo, “because you can use it for absolutely everything and it’s helped so many women in cooperatives achieve financial independence.”

Movement is also a key part of caring for our bodies; while sports provide physical fitness, practices such as contemporary dance therapy and yoga offer an emotional workout too, particularly when fully explored. Of the eight limbs of yoga, most white Westerners practice just a few – asana (the postures) and perhaps pranayama (breathing) and dhyana (meditation), unaware of its moral and spiritual dimensions, and there have been conversations around cultural appropriation of yoga. In our Industry Insight piece, we profile yoga teacher Nadia Gilani, who champions access to all.

Community

Writer Alicia A. Wallace argues that we can’t fully meet the needs of our souls, minds, or bodies on our own, and that caring for one another creates a much-needed sense of belonging. “It reminds us that we weren’t meant to walk these paths alone, but to learn

from and care for one another as we find better ways to live together,” she writes on Healthline.com.

Coming together outdoors is one of the ways we can do just that. Wild Awake runs outdoor camps and experiences such as stargazing, seaweed foraging, and forest bathing, centred on care for the environment and each other. “Wild Awake is all about developing a deeper relationship with the Earth, because that not only motivates one to fight for it and to care for it, but it also gives one that sense of belonging, which is deeply and radically healing,” says Shasha Du, the San Francisco nonprofit’s co-founder and creative director.

Community cohesion doesn’t have to be that adventurous; it can be cultivated closer to home. In São Paulo, home gardeners created the Horta das Corujas (Garden of Owls) to democratise public spaces and overcome barriers to social integration. Derek Haynes from North Carolina, whose Instagram handle is The Chocolate Botanist, told the Guardian: “Black folks gardening is … a radical act. We are returning to a connection to the land that was snatched away from us by hatred and racism.” In many southern states of the United States, public access to unfenced land – and therefore foraging – has been illegal since the mid 19th century, when enslaved people were emancipated, so the rise of community gardens and foraging among their descendants is a form of activism.

Supporting young people is a key part of bringing communities together. Amsterdam-based Comfy Community describes itself a “nomadic community centre” that works with creative young adults to provide events, workshops, and “uplifting content”. Self-discovery coach Calypso Barnum-Bobb focuses on “helping people to discover and express their personal power so they can create lives filled with freedom, fulfilment and abundance.” DJ and broadcaster Vanessa Maria, as well as sharing her love for underground UK music, hosts a music and mental health related podcast and documentary series, Don’t Keep Hush, sparking discussion around music and mental health.

Planet

As humans and communities, if we understand that we must do more than simply survive, we need to thrive, then surely sustainability” is not enough for the planet either. Even initiatives such as Earth Overshoot Day – the date each year when humanity exhausts the resources that Earth can regenerate during a year – position the planet as a resource, rather than a living ecosystem that deserves to thrive. “Regeneration goes beyond sustainability and mitigating harm, to actively restoring and nurturing, creating conditions where ecosystems, economies, and people can flourish,” as the Regeneration Rising report by brand consultancy Wunderman Thompson points out. “Flourish” is the operative word. Speaking at the September 2022 Zero Waste Conference in Vancouver, Michael Pawlyn, expert in regenerative design and biomimicry, and co-author of a book by the same name, called for humans to “co-evolve with nature, while recognising our role in the partnership.”

How does that role look? Environmentalist Paul Hawken assessed a multitude of climate solutions as part of Project Drawdown and told National Geographic that regenerative agriculture practices are “by far the single greatest solution to the climate crisis.” In his book English Pastoral, farmer James Rebanks, who offers regenerative farming courses, says that what he calls “benign inefficiency or good stewardship” means that “farms can allow a great many wild things to live in and around them.” The Wildfarmed project in the UK and France works with farmers to help them embrace regenerative practices that improve wheat quality, soil quality, and ecosystems.

In the Brazilian Amazon region, the lab.sonora residency, mediated by curators, ecologists, and Indigenous leaders, offers an artistic immersion in communities and environmental reserves. Its parent organisation, Labverde, aims to foster new ways of existence and interaction with the environment, and new approaches to maintaining fragile ecosystems; lab.sonora focuses on building a new soundscape for the Amazon. And the Krater collective in Ljubljana, Slovenia, hosts a thriving and diverse community of eco-social practitioners – read more about Krater in this edition’s Talent profiles.

If young people – from farmers to designers – are leading the charge, what does this mean for bigger brands and businesses? Is it enough for them to sell the outcomes of regenerative practices, or does the capitalist model itself need a regenerative rethink?

Having founded 1% for the Planet – an initiative in which companies donate 1% of their turnover to environmental causes – founder of Patagonia, Yvon Chouinard, recently announced that (almost) 100% of his company’s shares will be invested in fighting the climate crisis – a move company chair Charles Conn called ‘the future of business.’ Publicly listed companies are legally obliged to serve shareholder’s ‘best interests’ – often interpreted as profit. B Corp is trying to change this. Certification requires creates a legal obligation for directors to consider the interests of all stakeholders, not just shareholders, in their decisions – to consider people and planet alongside profit. And the Boardroom 2030 model calls for those stakeholders to be represented at the highest level, whether

they are young people, employees, representatives from marginalised groups, members of the local community or even advocates for the more-than-human world.

If we’re going to co-create a flourishing planet, we need business models that enable souls, minds, bodies and communities to thrive.

Born in Hong Kong into a wealthy family, educated in London and Japan and influenced by the Arts and Crafts Movement, Bernard Leach (1887–1979) championed an anti-industrial approach to ceramics that influences makers all over the world to this day. ‘Factories have practically driven folk-art out of England,’ he wrote in A Potter’s Book. ‘The artist-craftsman, since the day of William Morris, has been the chief means of defence against the materialism of industry and its insensibility to beauty.’ Conceding that ‘perfection’ was more than possible at the hands of machines, Leach maintained that there was a ‘higher, more personal, order of beauty,’ only achievable when craftsmen made pots by hand.

Born in Hong Kong into a wealthy family, educated in London and Japan and influenced by the Arts and Crafts Movement, Bernard Leach (1887–1979) championed an anti-industrial approach to ceramics that influences makers all over the world to this day. ‘Factories have practically driven folk-art out of England,’ he wrote in A Potter’s Book. ‘The artist-craftsman, since the day of William Morris, has been the chief means of defence against the materialism of industry and its insensibility to beauty.’ Conceding that ‘perfection’ was more than possible at the hands of machines, Leach maintained that there was a ‘higher, more personal, order of beauty,’ only achievable when craftsmen made pots by hand.

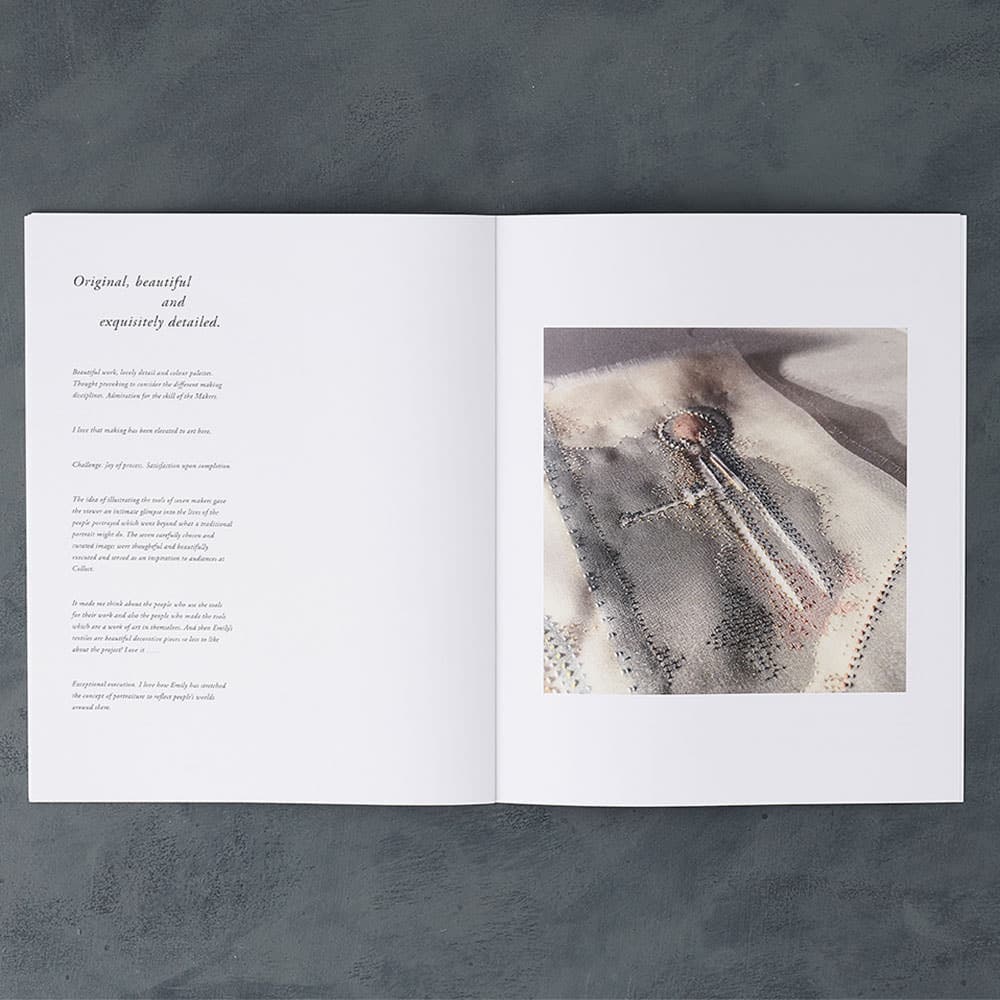

The book comprises six chapters – London, Tokyo, Copenhagen, New York, Sydney and São Paulo – cities chosen for their vibrant ceramics scenes. For each one, I have written an introductory essay telling just one of the many stories of pottery in that city and then profiled some of the most exciting contemporary studio potters working in each city today. My hope in doing so is to tell a more inclusive story of clay, recognising the diversity of its craftsmen – and women.

The book comprises six chapters – London, Tokyo, Copenhagen, New York, Sydney and São Paulo – cities chosen for their vibrant ceramics scenes. For each one, I have written an introductory essay telling just one of the many stories of pottery in that city and then profiled some of the most exciting contemporary studio potters working in each city today. My hope in doing so is to tell a more inclusive story of clay, recognising the diversity of its craftsmen – and women.